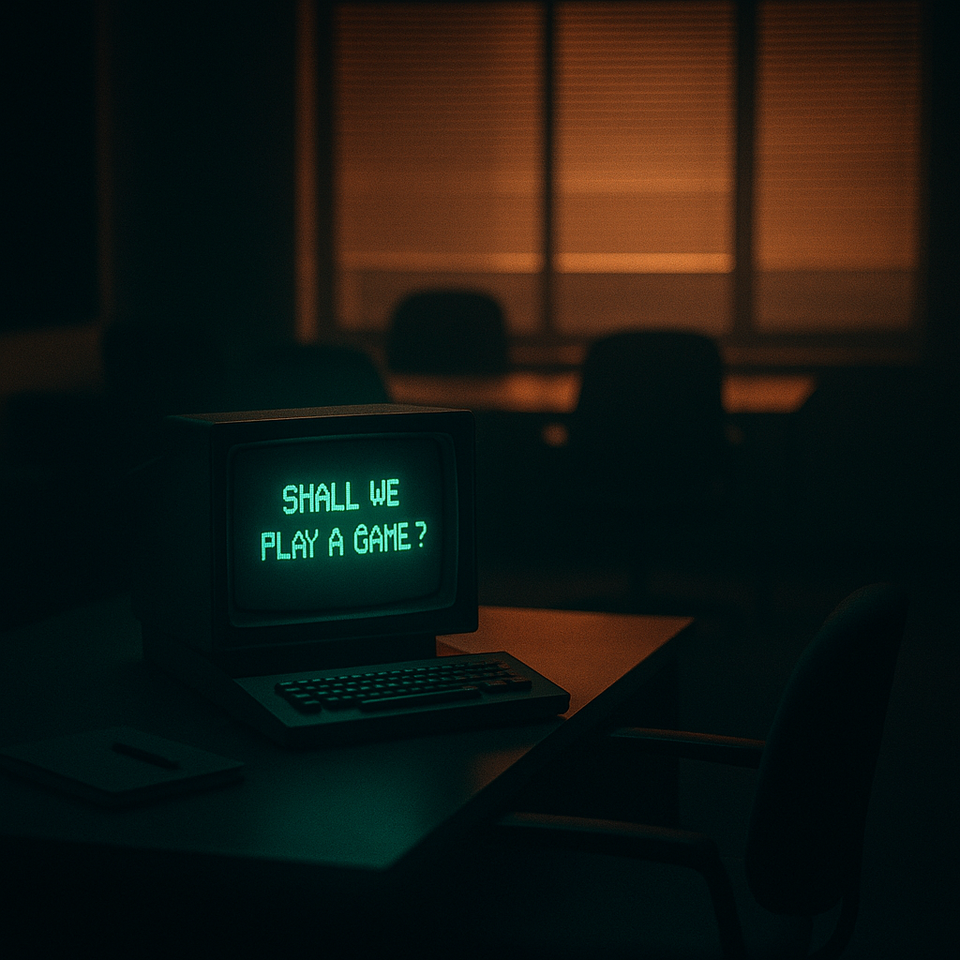

The Product War Game: Shall We Play?

In WarGames (1983), Matthew Broderick plays a young hacker who accidentally accesses a military supercomputer named Joshua, capable of simulating nuclear war. Believing it is just a game, he triggers a countdown to all-out global conflict.

After running thousands of simulations, each ending in total annihilation, Joshua delivers one of the most memorable lines in 1980s cinema:

“A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.”

That line still resonates because it reveals something timeless about conflict. We often enter battles believing we can win, only to realize the act of fighting destroys the very thing we were trying to protect.

The Arms Race of Product Teams

Most product conflict starts with good intentions.

Product wants clarity.

Engineering wants feasibility.

Design wants integrity.

Leadership wants predictability.

None of these goals are wrong, but when alignment fades, the room divides. Toxicity begins to surface, and people start optimizing for survival instead of outcomes.

All of a sudden, information becomes classified. Decisions are defended like territory. You do not even realize it is happening until your daily stand-up sounds like a peace negotiation.

Mutually Assured Dysfunction

Teams develop their own deterrents: passive resistance, selective transparency, quiet disengagement. No one attacks directly, but no one trusts either.

Velocity slows. Morale fades. Meetings multiply.

The tragic part is that toxic behaviors rarely come from bad people. They come from exhausted ones who have stopped being heard.

And when that happens, teams stop innovating.

Seeing This in Practice

I saw this firsthand when executives from different business functions could not get along. What started as healthy tension over priorities devolved into something far more destructive.

First, the sides stop sharing information openly. Discussions turn into territorial negotiations. Each side starts optimizing ego over outcome.

The dysfunction does not stay at the executive level. It cascades through the organization. Individual contributors pick up on the tension and start choosing sides. Cross-functional collaboration becomes performative, with everyone going through the motions while protecting their own teams.

Once the cycle starts, it feeds on itself. Every defensive move justifies the next one. Every withheld piece of information breeds more suspicion.

By the time everyone realizes what is happening, the pattern is entrenched, and in the end, nobody wins.

What It Looks Like When You Are In It

It is often hard to spot when a culture turns toxic, but the signs are always there. Trust erodes, feedback dies, and people protect themselves instead of the product.

You will know you are in a war when:

• The same arguments repeat endlessly

• Winning means the other side looks bad

• Information gets weaponized

• Every meeting leaves you exhausted

If this sounds familiar, you have to decide how not to play.

How Not to Play

In WarGames, Joshua stops because it learns the game is unwinnable. Healthy teams reach the same realization. They pause and ask:

• Are we debating to understand, or to be right?

• Are we protecting process, or serving purpose?

• Are we being kind to each other?

When teams can ask those questions without defensiveness, the simulation ends.

But learning only works when it is safe to be wrong.

Taking It Down to DEFCON 5

When it is time to act, leaders must model the behavior they want to see. It is not about calming people down; it is about creating safety so the right conversations can happen.

Model vulnerability

Start by showing that it is safe to be wrong.

- Say things like, “I was wrong about that feature,” or “You raised that concern and I dismissed it. You were right.”

- Use these moments to reset the tone. When leaders own mistakes publicly, the team learns that humility is part of the process, not a weakness.

Build safety

Encourage curiosity instead of blame.

- Hold blameless post-mortems after failures.

- Revisit past decisions when new data emerges.

- Recognize people who change their minds when presented with better evidence.

Psychological safety is not a policy. It is a pattern people learn from how you respond under pressure.

Treat each other with respect, and name the pattern

When tension builds, pause the debate and describe what you see instead of judging motives. For example:

“Every time Engineering raises a concern, Product responds with a customer commitment. Then Engineering goes quiet. What is happening there?”

This approach makes the issue visible without blaming anyone. If possible, invite a neutral observer or facilitator to help frame these moments objectively. The goal is to help the team notice its own behavior, not to assign fault.

Agree on what winning means

Teams often argue because they are using different scoreboards.

Take time to define success together for customers, the business, and the team. Write it down. Make it specific. Revisit it whenever conflict resurfaces. Shared definitions turn arguments into alignment exercises.

Establish new norms with consequences

New rules only work if they are real.

- “We share context before decisions, not after.”

- “We assume good intent and ask questions before attributing motives.”

- “If we cannot resolve something in two meetings, we escalate with a clear framework.”

Assign someone to uphold these norms. Accountability must be visible, or the old habits will return.

Rebuild through small wins

Start small. Pick a low-stakes project where collaboration can shine again. Let people experience what healthy teamwork feels like in action.

Trust does not rebuild through workshops. It rebuilds through shared success.

Measure and iterate

Check in regularly. Ask, “Do you feel heard?” and “Has conflict become more productive?” Track the responses over time. Improvement is a signal that culture is shifting.

Know when to leave

If the dysfunction is structural and leadership refuses to change, protecting your career and mental health might mean finding a healthier environment.

That is not quitting. That is strategy. Sometimes the only winning move is to find a better game.

The Only Winning Move

Refusing to play does not mean retreating. It means opting out of cycles that destroy trust, politics, ego, and blame.

Whether you are leading the recovery or surviving the dysfunction, the insight is the same. You get to choose how much of yourself you sacrifice to the war.

Your competitors are not waiting for you to resolve dysfunction. Your customers are not taking sides.

So, the next time a meeting feels like mutual destruction, ask yourself:

Am I escalating, or am I learning?

And if you are stuck in a system that punishes learning, ask yourself:

How long am I willing to stay?

In the end, refusing to play or knowing when to leave may be the most strategic move you will ever make.

And maybe, just maybe, as Joshua suggests, you will get to play a nice game of chess.